The Cows of Medellín

|

| We landed on the 17th floor in the hilly Sabaneta neighborhood. |

We had toyed with the idea of taking the ~one hour flight from Cartagena to Medellín but chose the bus instead as the Mexican and South American bus systems are in a whole different league than ridin' da hound in the USA. The buses are new, gigantic and the seats are quite a bit larger than those in the cheap seat section of the airlines. For short flights, one must also consider the hassle/wasted time of checking in at the airport and what that entails.

The buses stop at local restaurants for an hour here and there, there is wi-fi, sometimes very loud telenovelas on the box and you get to leisurely watch the scenery roll by. All things considered and being in no particular hurry, we went with Autobus Expresso Brasilia for the 391 mile journey. The voyage ended up taking seventeen hours, about seven hours too long, due largely to an extremely clogged, one way up, one way down, mountain pass.

Got to see a bit of rural Columbia.

Dropped off passengers in lots of small towns.

Dropped off passengers in lots of small towns.

Modern guerrilla warfare in rural Colombia originated in the form of agrarian disputes and dates back to the 1920 's. A real baddie in all of what is known here as La Violencia was the United Fruit Company now known as Chiquita Brands International. They had a lot to do with what we now call banana republics.

Modern guerrilla warfare in rural Colombia originated in the form of agrarian disputes and dates back to the 1920 's. A real baddie in all of what is known here as La Violencia was the United Fruit Company now known as Chiquita Brands International. They had a lot to do with what we now call banana republics.

Dropped off passengers in lots of small towns.

Dropped off passengers in lots of small towns. Modern guerrilla warfare in rural Colombia originated in the form of agrarian disputes and dates back to the 1920 's. A real baddie in all of what is known here as La Violencia was the United Fruit Company now known as Chiquita Brands International. They had a lot to do with what we now call banana republics.

Modern guerrilla warfare in rural Colombia originated in the form of agrarian disputes and dates back to the 1920 's. A real baddie in all of what is known here as La Violencia was the United Fruit Company now known as Chiquita Brands International. They had a lot to do with what we now call banana republics.As the tragic, often murderous and heartbreaking tales of unrequited love that Latin telenovelas seem to favor, blared away, I brought out my Spanish language anthology of the world's classic short stories. I pondered if I was showing my age by reading a BOOK. Everyone else on the bus, and I mean everyone from grandma right on down to little Pablito was right swiping, left swiping or otherwise doing something on their devices that made loud and annoying PINGS.

I finished The Purloined Letter by former University of Virginia student and celebrated ne'er do well Edgar Allen Poe as well as Hans Christian Anderson's The Ugly Ducking. A couple of hours out of Medellin, I started ¡Adiós, Cordera! written in 1892 by Spanish author Leopoldo Alas.

Alas' highly creative style and use of many indirect objects left me confused as to who was who in the story. For starters, Cordera means lamb in Spanish. At first I thought it was a lamb and two cows listening to the buzzing of the new fangled telegraph wires.

Turns out gentle reader that Cordera is the family cow and is tended to by a peasant brother and sister team. I translate here in a C+ kind of way:

"Cordera had lived through a great deal. She was much more formal and mature in years than her companions and kept her distance from the civilized world. She looked from afar at the telegraph pole as an inanimate thing not even worth scratching against. On all fours for hours on end, she became an expert in pastures and knew how to make the best use of her time.

She meditated more than she ate and enjoyed living under the tranquil sky of her pasture. It was as if she was giving comfort to her soul, something even the brutes of this world possess. Were the idea not profane, it would be possible to say that the thoughts of the matronly cow resembled Horace's most calming and doctrinal odes.

Turns out gentle reader that Cordera is the family cow and is tended to by a peasant brother and sister team. I translate here in a C+ kind of way:

"Cordera had lived through a great deal. She was much more formal and mature in years than her companions and kept her distance from the civilized world. She looked from afar at the telegraph pole as an inanimate thing not even worth scratching against. On all fours for hours on end, she became an expert in pastures and knew how to make the best use of her time.

She meditated more than she ate and enjoyed living under the tranquil sky of her pasture. It was as if she was giving comfort to her soul, something even the brutes of this world possess. Were the idea not profane, it would be possible to say that the thoughts of the matronly cow resembled Horace's most calming and doctrinal odes.

It was her pleasure to graze quietly, without lifting her head to look about in idle curiosity. She would carefully select the choicest morsels and then lie down to meditate. All she cared to do was to exist, to enjoy the delight of simply not suffering. Other things were dangerous undertakings."

Why is this important you may legitimately ask?

Take a look again at this picture. Apartment buildings are everywhere except in the cow pasture in our front yard. Medellin now stretches for dozens of miles along the Aburrá Valley. Back in the day, our Sabaneta neighborhood would have been a small village, populated by wealthy cattle families that built haciendas and fincas. I am guessing that this pasture is a hanging on by its fingernails vestige of pre-urbanized Sabaneta.

Why is this important you may legitimately ask?

Take a look again at this picture. Apartment buildings are everywhere except in the cow pasture in our front yard. Medellin now stretches for dozens of miles along the Aburrá Valley. Back in the day, our Sabaneta neighborhood would have been a small village, populated by wealthy cattle families that built haciendas and fincas. I am guessing that this pasture is a hanging on by its fingernails vestige of pre-urbanized Sabaneta.

Why is this cow pasture still here? There are about 20 cows and a few hacienda type houses on the property but it has to be worth millions to someone. Is the family of grandpa allowing him to to die on the old farmstead before they sell it to developers? The kids will receive millions and the developers get to build one more lifestyle community with an Infinity pool on the roof? I posed these questions to a maintenance man that was doing preventive insect control in our apartment one morning. Guess whose name came up? Yup, like many things ....Pablo Escobar.

The point is, and I did have a point at some point, is that after reading ¡Adiós, Cordera! the lives of these Colombian cows are now on my daily radar. See how, in the picture above, the cows have grazed the paddock on the right down to its brown roots, while the paddock on the left is lush and green? Well, it was late-breaking news when a farm worker came and rotated them into the lush pasture on the left. Talk about the grass being greener on the other side. Happy cows, tails swaying and all.

The point is, and I did have a point at some point, is that after reading ¡Adiós, Cordera! the lives of these Colombian cows are now on my daily radar. See how, in the picture above, the cows have grazed the paddock on the right down to its brown roots, while the paddock on the left is lush and green? Well, it was late-breaking news when a farm worker came and rotated them into the lush pasture on the left. Talk about the grass being greener on the other side. Happy cows, tails swaying and all.

At certain times of the day, they all will sit down in a group and chill for an hour or so...."hey Lilly, the cows are taking a break!" I report. When they go for a lick of salt or a leisurely swill of twenty gallons of spring water, it generates equal amounts of glee in apartamento #1701 (the tap water here in Medellin is awesome, reminds me of the Catskill tap water that flowed into NYC back in the day). It rains here almost every day, which is great news for the depleted pasture, but even greater news for me, because the cows wait it out under a copse of trees! Oh, the joy of it all.

I can't help think about Cordera, an expert in pastures, making the best use of her time back in 1892. Meditating, eating only the choicest morsels, existing, enjoying the delight of simply not suffering and keeping her distance from the civilized world. As other things were dangerous undertakings.

Not so fast!

One day the farm workers came and built that loading corral in the upper right of the picture.

Were these Medellín vacas, after all of that Elysian meditation, fated to become rib-eyes as Cordera did in 1892?

Were these Medellín vacas, after all of that Elysian meditation, fated to become rib-eyes as Cordera did in 1892?

In the story, the mother of Rosa and Pinín, the peasant twin caretakers of Cordera, dies unexpectedly. The father can no longer afford the rough hut that the family shares with Cordera and has to sell her to pay the rent. Later, the twins are alone back up in the pasture:

"Suddenly, the locomotive whistled and smoked and the train appeared. In a closed boxcar, the twins glimpsed the heads of the cows that bewilderingly peered through the narrow air vents.

'Goodbye, Lamb!' cried Rosa, imagining her friend, the grandmotherly cow.

'Goodbye, Lamb!' yelled Pinín, with the same faith, brandishing his fists at the train that flew toward Castile.

'Goodbye, Lamb!' cried Rosa, imagining her friend, the grandmotherly cow.

'Goodbye, Lamb!' yelled Pinín, with the same faith, brandishing his fists at the train that flew toward Castile.

The tearful boy, more conscious than his sister of the villainy of the world, cried out:

'They’re taking her to the slaughterhouse….beef for the gentlemen, the priests … for those who have come back rich from the Americas'.

'Goodbye, Lamb!'

'Goodbye, ‘Lamb!'

'Goodbye, Lamb!'

'Goodbye, ‘Lamb!'

Rosa and Pinín gazed with rancor at the railway line and the telegraph, symbols of a malevolent world that had snatched from them, that had devoured their companion of so many pastoral solitary hours, of so much silent tenderness... to convert her into beef in order to gratify the appetites of rich gluttons.

'Goodbye, Lamb!'

'Goodbye, Lamb!'

Yeah, yeah, I know in the era of Pablo Escobar and a myriad of civil wars, Medellín was the most dangerous city in the world. Now days though, Medellín offers a staggering amount of edible fruits, some recognizable, others totally foreign. We bought this cornucopia of fruits, vegetables and spices at a farmer's market for $21.00.

Yeah, yeah, I know in the era of Pablo Escobar and a myriad of civil wars, Medellín was the most dangerous city in the world. Now days though, Medellín offers a staggering amount of edible fruits, some recognizable, others totally foreign. We bought this cornucopia of fruits, vegetables and spices at a farmer's market for $21.00.

Parque de los Pies Descalzos, or the barefoot park is an inner city park that allows city dwellers the chance to walk around....barefoot and have a little quiet Zen time.

The central plaza in our neighborhood Sabaneta. In days of yore, it would have been a small town south of Medellín until it was gobbled up by the exburbs. The park has a very European feel with the retirees whiling away the mornings in the cafes, solving the problems of the world with a double espresso of Colombian Gold coffee.

I don't know why I had never heard about the gondola system in Medellín. It was created, with a nod to the ski areas of Switzerland, to link the Metro train system with the impoverished and undeveloped comunas (neighborhood districts) that sprawl on the steep hills of the valley. Some of these barrios did not even have a reliable public bus system and thus left the residents isolated and threatened by gang rule. This Metrocable system is credited with helping transform Medellín from the most dangerous city in the world to one of the most innovative in South America.

It costs less than a dollar to ride and offers great views of the city as you travel from the valley to the top of the mountains. We did get the feeling of slum tourism though; riding safely high above the neighborhood known as Comuna 13, peeping into the porches and rooftops of poor people, like they were in some kind of a zoo.

It costs less than a dollar to ride and offers great views of the city as you travel from the valley to the top of the mountains. We did get the feeling of slum tourism though; riding safely high above the neighborhood known as Comuna 13, peeping into the porches and rooftops of poor people, like they were in some kind of a zoo.

What, with Pablo Escobar fighting with competing drug cartels as the military tried to control both of them, left wing revolutionaries fighting with privately funded right wing militias, Colombia was a dangerous place in the 1980's. If Medellín was one of the most violent places on earth during that time (Caracas, Venezuela now holds that dishonor), one Medellín neighborhood in particular ranked as the deadliest of them all: Comuna 13.

What, with Pablo Escobar fighting with competing drug cartels as the military tried to control both of them, left wing revolutionaries fighting with privately funded right wing militias, Colombia was a dangerous place in the 1980's. If Medellín was one of the most violent places on earth during that time (Caracas, Venezuela now holds that dishonor), one Medellín neighborhood in particular ranked as the deadliest of them all: Comuna 13.

I don't know why I had never heard about the gondola system in Medellín. It was created, with a nod to the ski areas of Switzerland, to link the Metro train system with the impoverished and undeveloped comunas (neighborhood districts) that sprawl on the steep hills of the valley. Some of these barrios did not even have a reliable public bus system and thus left the residents isolated and threatened by gang rule. This Metrocable system is credited with helping transform Medellín from the most dangerous city in the world to one of the most innovative in South America.

It costs less than a dollar to ride and offers great views of the city as you travel from the valley to the top of the mountains. We did get the feeling of slum tourism though; riding safely high above the neighborhood known as Comuna 13, peeping into the porches and rooftops of poor people, like they were in some kind of a zoo.

It costs less than a dollar to ride and offers great views of the city as you travel from the valley to the top of the mountains. We did get the feeling of slum tourism though; riding safely high above the neighborhood known as Comuna 13, peeping into the porches and rooftops of poor people, like they were in some kind of a zoo. What, with Pablo Escobar fighting with competing drug cartels as the military tried to control both of them, left wing revolutionaries fighting with privately funded right wing militias, Colombia was a dangerous place in the 1980's. If Medellín was one of the most violent places on earth during that time (Caracas, Venezuela now holds that dishonor), one Medellín neighborhood in particular ranked as the deadliest of them all: Comuna 13.

What, with Pablo Escobar fighting with competing drug cartels as the military tried to control both of them, left wing revolutionaries fighting with privately funded right wing militias, Colombia was a dangerous place in the 1980's. If Medellín was one of the most violent places on earth during that time (Caracas, Venezuela now holds that dishonor), one Medellín neighborhood in particular ranked as the deadliest of them all: Comuna 13.Thousands of villagers in the countryside were displaced by the violence and escaped to Medellín looking for work. They arrived with the shirts on their backs and built illegal housing on the very steep hills on the outskirts of town. They used whatever construction materials they could find to build shelters on top of one another, sewage often ran down the streets and there was limited to no access to public transportation, hospitals and grocery stores

The warren like layout of the hills and the steep incline of stairs twisting and turning in this vast maze gave many criminals places to hide and ambush police and hence it became a no-go zone. In 2002 there was basically a war declared on Comuna 13 by the military that included a tank and armed helicopters. It ended in mass civilian casualties but started a slow revitalization, which included adding the cable car system and in 2011 they built 6 escalators that replaced some the often jury rigged steps carved in the hillside.

These escalators opened up the neighborhood to the curious. Young locals who wanted more than the gang life started painting murals, break dancing, rapping and giving tours. As such it is now a thing. Did I say that this slog is steep?

These escalators opened up the neighborhood to the curious. Young locals who wanted more than the gang life started painting murals, break dancing, rapping and giving tours. As such it is now a thing. Did I say that this slog is steep?

We went on a Sunday and instead of us looking down from the cable car on the locals, they looked down on us from their porches, like we tourists were the ones in the zoo. From what I gather, it is still a rough game, a work in progress, and I wouldn't want to be a wanderin' around there with a fanny pack and a iPhone after dark.

These escalators opened up the neighborhood to the curious. Young locals who wanted more than the gang life started painting murals, break dancing, rapping and giving tours. As such it is now a thing. Did I say that this slog is steep?

These escalators opened up the neighborhood to the curious. Young locals who wanted more than the gang life started painting murals, break dancing, rapping and giving tours. As such it is now a thing. Did I say that this slog is steep?We went on a Sunday and instead of us looking down from the cable car on the locals, they looked down on us from their porches, like we tourists were the ones in the zoo. From what I gather, it is still a rough game, a work in progress, and I wouldn't want to be a wanderin' around there with a fanny pack and a iPhone after dark.

On a less threatening note, we took another cable car to arrive at Arví Park, 40,000 acres of ecological nature preserve at 7500 feet; a small part of it is mountainous jungle still in its primordial state. As I like parks like this more than people, I am glad that they didn't allow it to become a slum, 'cause there are slums all around it.

One cool thing to do in Arví that piqued my interest was the Pre-Hispanic Trail, which offers glimpses of period buildings, waterworks, burial grounds, platforms and gardens. I gather that aboriginal people have been a wanderin' around these mountains for~12,000 years. I wanted to hike at least part of it and take a little look around but guides told us that people get lost in the park all the time and it was getting late, so we settled for Colombian Espresso in their jungle coffee shop.

Got wild and crazy ......

....and whooped it up on by 64th birthday.

One cool thing to do in Arví that piqued my interest was the Pre-Hispanic Trail, which offers glimpses of period buildings, waterworks, burial grounds, platforms and gardens. I gather that aboriginal people have been a wanderin' around these mountains for~12,000 years. I wanted to hike at least part of it and take a little look around but guides told us that people get lost in the park all the time and it was getting late, so we settled for Colombian Espresso in their jungle coffee shop.

Got wild and crazy ......

....and whooped it up on by 64th birthday.

We had of course read about the strikes and small riots that have been breaking out in Medellín; the causes being the usual suspects of income inequality, police and political corruption and Covid restrictions. The city is so big and as we were ensconced in a far suburb, so we only read about them in the paper, One day however, after getting some Zen time in the Barefoot Garden, we noticed hundreds, maybe a few thousand, students attempting to block rush hour traffic in a disruptive maneuver known here as un bloqueo.

The demonstrators begin to set off what sounded like M-80s and other fireworks and they were successful for about 20 minutes until the tear gas brigade arrived. We calmly headed the other direction in pursuit of a Happy Hour somewhere. However, for a dozen or so blocks, the wind carried the tear gas and we were lightly affected along with the other pedestrians. Seemed like no big deal to them.

On our way south to Bogotá we stopped in the picturesque town of Salento for several days, located in the eje cafetero, the heart of Colombia's Coffee Growing Region. Salento offers a quiet and relaxed lifestyle, hiking in the famed Cocora Valley and of course the coffee tours, which makes it one of the most popular tourist destinations in Colombia. Weary city dwellers from Colombia's megalopolis' love to get a little peace and quiet in places like our Airbnb above.

The Cocora Valley is the main location where the national tree of Colombia, the Quindío wax palm, can be found. Once abundant in the Colombian Andes, the world's largest palm tree has become endangered due to jungle canopy deforestation in order to provide pastures for cattle. They grow so tall because they used to have to compete for the sunlight above the deciduous canopy. The mountain people still chop down the trees to make wax candles, but the second problem is the extensive use of the palms leaves in the Catholic celebrations of Palm Sunday. Evidently the faithful pulled the leaves from the trees that they could reach and thereby damaged the young plants to death. Alas gentle reader, Rib-eyes and Religion.

The Cocora Valley starts at about 6500 feet and these mountains must rise a few thousand feet higher. I watched a few You Tube videos of the most popular hikes. They looked like muddy slogs lasting up to eight hours and one has to cross many streams balancing on slippery logs holding on to a cable and sometimes without a cable. Joy/Risk/Effort problem here.

The Cocora Valley starts at about 6500 feet and these mountains must rise a few thousand feet higher. I watched a few You Tube videos of the most popular hikes. They looked like muddy slogs lasting up to eight hours and one has to cross many streams balancing on slippery logs holding on to a cable and sometimes without a cable. Joy/Risk/Effort problem here.

So for the first time since Camp Yonanoka, outside of Boone North Carolina, circa 1970, horseback riding it was.

Our guide up to the cloud forests. He had his own language with the horses, whistles that meant different things and a long stick. On tricky cliffs he would hold the horse's tail. On several of these precipices and crossing bouldery streams I sure was hoping that our mounts were the most sure footed of his string. Lilly wondered what would have happened if the horses tumbled off? Nothing...like who are you going to sue?

This caballero was a bit younger than me, but not by much. He said he walks the various trails two or three times a day. Reminds me of the Sherpas in Nepal, who might carry the "summiteers" gear up Mount Everest several times a season......

.....so we summiteers can get a shot like this.

.....so we summiteers can get a shot like this.

.....so we summiteers can get a shot like this.

.....so we summiteers can get a shot like this.

Finished up in the old colonial part of gigantic Bogotá.

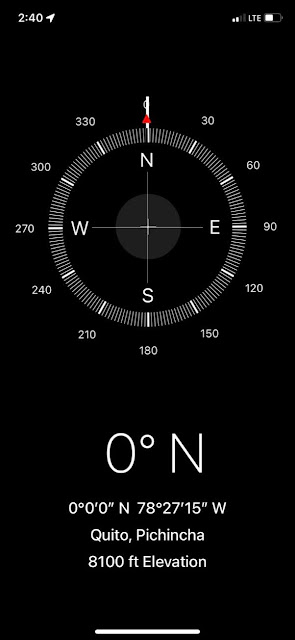

Inside the compound. Lots of steel doors to keep out rascals. At 8660 feet it was rainy and quite chilly at night, so a fire in late afternoon through first thing in the morning was in order.

Inside the compound. Lots of steel doors to keep out rascals. At 8660 feet it was rainy and quite chilly at night, so a fire in late afternoon through first thing in the morning was in order.

Inside the compound. Lots of steel doors to keep out rascals. At 8660 feet it was rainy and quite chilly at night, so a fire in late afternoon through first thing in the morning was in order.

Inside the compound. Lots of steel doors to keep out rascals. At 8660 feet it was rainy and quite chilly at night, so a fire in late afternoon through first thing in the morning was in order.

One thing I will remember about the mountainous part of Colombia is just how fuckin' steep some of these neighborhoods could be. Huffin' and a Puffin' with a backback full of rum and groceries at 8800 feet.

Our neighborhood, La Candelaria, had several colleges and universities near by.

This combination of students, old money and tourists provides many hipster coffee shops

This combination of students, old money and tourists provides many hipster coffee shops

As you look up from anywhere in the city, Monserrate Hill dominates. Long considered sacred by the indigenous Muisca people, the Spanish built a church there in the 17th century. The faithful climbed the steps to the pilgrim destination at 10, 300 feet.

The steep steps take from 1-3 hours to climb, depending on grandpa's stamina. I am decidedly not a pilgrim so as luck would have it, in 1929 someone from Switzerland proposed cable cars and later in the 1950s the gondola system was added.

The restaurant at the top gets good reviews.

La Puerta Falsa opened in 1816, has 20 seats and is the go to place for one of Colombia's national dishes: Ajiaco.

La Puerta Falsa opened in 1816, has 20 seats and is the go to place for one of Colombia's national dishes: Ajiaco.

La Puerta Falsa opened in 1816, has 20 seats and is the go to place for one of Colombia's national dishes: Ajiaco.

La Puerta Falsa opened in 1816, has 20 seats and is the go to place for one of Colombia's national dishes: Ajiaco.

To generalize, the foundation of Colombian food is hearty meats and starches. I think the only spice that they use is salt. The Ajiaco above at La Puerta Falsa boasts of "three different kinds of potatoes" and the tamale above the soup includes rice, corn meal. yucca and potatoes. The Ajiaco has plenty of shredded chicken, the potatoes, yucca and the corn cob (not Virginia sweet corn, but the kind they make Colombian tortillas called arepas). It is accompanied by arepas and butter, boiled white rice, crema and oddly enough, capers. The avocado is your salad and the drink on the right is chicha, a lightly fermented corn drink As far as I could tell, not a spice in any of it. I think that the Ajiaco was ~$7.00 and was great for a light little snack before high altitude, chilly, rainy adventures.

As we are fans of highly spiced foods from places like Mexico, Thailand and India, we carried with us a large jar of crushed red pepper flakes...much to the amusement of the waiters. We can't wait to get back to Mexico for some tacos al pastor with a side of mole and pickled jalapeños!

Thanks for stopping by

Comments