Want to Go Camping with this Motley Crew?

Whew! Sweet Reader, what a show I stumbled on when I chose to live on Kilauea Volcano!

I am working on a blog detailing the closing of Kalani and the the destruction of Lower Puna that continues as I write to you from the Laupahoehoe library. I have been living in my camper van with 4 chefs and other motley crew members from Kalani as we ponder our next move and watch Pele dance a dance that changes by the hour.

It all has such a surreal aura about it, I thought I would re-post this blog from a few years ago, as I camp in a very weird (but safe) situation.

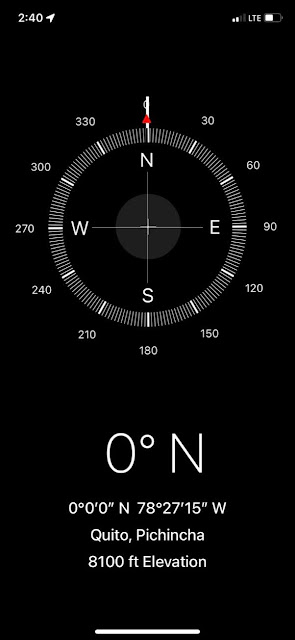

Now, where am I again?

Recently a young woman named Angela and I went on a camping trip to an isolated valley in the north part of the Big Island. As we were walking along the stream things began to change in the most uncanny of ways. We came upon a village of about twenty adobe houses, which looking back, should have been our first clue that we were entering another vortex because Hawaii doesn’t have adobe houses. They were built on a bank of river that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names and in order to indicate them we had to point.

Strangely, as we entered the village there were families of ragged gypsies going about their daily village rituals in an almost stone age kind of way. A heavy gypsy with an untamed beard and sparrow hands, introduced himself as Melquíades. He then proceeded to put on a bold public demonstration of what he himself called the eighth wonder of the learned alchemists of Macedonia. It was two large magnets. Melquíades went from house to house dragging the two metal ingots and we intruders as well as the villagers were amazed to see pots, pans, tongs and braziers tumble down from their places and beams creaked from the desperation of nails and screws trying to emerge and even objects that had been lost a long time appeared from where they had been searched for the most and went dragging along in turbulent confusion behind Melquíades’ magical irons.

We, this motley crew of idealists, ambitious people, adventurers, those with social resentments, even common criminals followed Melquíades deep into the Hawaiian rainforest where he unearthed a suit of fifteenth century armor which had all of its pieces soldered together with rust. Four or five men from the expedition managed to take the armor apart and they found inside a calcified skeleton with a copper locket containing a woman’s hair around its neck.

We, this motley crew of idealists, ambitious people, adventurers, those with social resentments, even common criminals followed Melquíades deep into the Hawaiian rainforest where he unearthed a suit of fifteenth century armor which had all of its pieces soldered together with rust. Four or five men from the expedition managed to take the armor apart and they found inside a calcified skeleton with a copper locket containing a woman’s hair around its neck.

We continued on and for ten more days but we did not not see the sun. The ground was a soft volcanic ash and the vegetation became thicker and thicker and the cries of the birds and the uproar of the monkeys became more and more remote and the world became eternally sad.

Then we went a week without speaking, listening attentively to the stories of Melquíades, of his innumerable trips around the world. He was a fugitive from all the plagues and catastrophes that had ever lashed mankind. He had survived pellagra in Persia, scurvy in a Malayan archipelago, leprosy in Alexandria, beriberi in Japan, bubonic plague in Madagascar, an earthquake in Sicily, a disastrous shipwreck in the Strait of Magellan. Sometimes he would stop and look at the choices between several paths and say “the main thing is not to lose our bearings”. Uh…..OK.

Exhausted by rigors of the hike and swelter of the jungle, we hung up our hammocks and slept deeply for the first time in two weeks. When we woke up we were speechless with fascination, because before us, surrounded by ferns and palm trees, was an enormous Spanish galleon.

Exhausted by rigors of the hike and swelter of the jungle, we hung up our hammocks and slept deeply for the first time in two weeks. When we woke up we were speechless with fascination, because before us, surrounded by ferns and palm trees, was an enormous Spanish galleon.

The old ship tilted slightly starboard, had hanging from its intact masts the dirty rags of its sails in the midst of the rigging. The hull, covered with an armor of petrified barnacles and soft moss, was firmly fastened to a surface of stones. The whole structure seemed to occupy its own space, one of solitude and oblivion, protected from the vices of time and the habits of birds. Inside, as we expeditionaries explored with careful intent, there was nothing but a thick forest of tropical flowers.

Propped up in the captain's chair was Úrsula, a merry, foul-mouthed and provocative woman, sitting there like a goddamned sultana of Persia. In her calloused and dirty hands was a gold crucible. One of the other white people in our group asked her what was in it.

Propped up in the captain's chair was Úrsula, a merry, foul-mouthed and provocative woman, sitting there like a goddamned sultana of Persia. In her calloused and dirty hands was a gold crucible. One of the other white people in our group asked her what was in it.

“Dog shit”, she replied.

There was silence, except for the chatter of the macaws and she continued:

“And now ladies and gentleman, we are going to show the terrible spectacle of the woman who must have her head chopped off every night at this time for one hundred and fifty years as punishment for having seen what she should not have and going beyond the limits of human knowledge.”

Just then, Úrsula’s son, José Arcadio appeared from a square door from below deck. When he was penniless, which was most of the time, we learned that he would enlist with a crew of sailors without a country and had been around the world sixty five times. Life at sea had saturated his memory with too many things to remember.

There was not a square inch of his body that was not covered with tattoos, front and back, forehead to toes, in words of several languages, intertwined in blue and red. Angela and I got to know José Arcadio quite well. He said that since his return home, he had not succeeded in being incorporated back into the family and as a result, he slept all day below deck and spent his nights in a near-by red light district, sleeping with the women who would pay him the most.

On the rare occasions when Úrsula got him to sit down at the table, he gave signs of radiant good humor, especially when he told about his adventures in remote countries. He had been shipwrecked and spent two weeks adrift in the Sea of Japan, feeding on the body of a comrade who had succumbed to heat stroke and whose extremely salty flesh as it cooked in the sun had had a sweet and granular taste. Under a bright noonday sun in the Gulf of Bengal his ship had killed a sea dragon, in the stomach of which they found the helmet, the buckles and the weapons of a Crusader. In the Caribbean he had seen the ghost of the pirate ship Victor Hugues, with its sails chewed by the winds of death, the masts chewed by sea worms and still looking for the course to Guadeloupe.

Úrsula would weep as if she was reading the letters that had never arrived and in which José Arcadio told about his deeds and misadventures. “And there was so much of a home here for you, my son”, she would sob, “and so much food thrown to the wild pigs”. But underneath it all, she could not conceive that the boy the gypsies took away was the same lout who would eat half a suckling pig for lunch and whose flatulence withered the flowers.

It then begin to rain for four years and eleven months and two days. José Arcadio spent much of this time below deck, examining things, trying to find a difference from their appearance on the previous day in the hope of discovering in them some change that would reveal the passage of time. He would call to Úrsula and Melquíades and to all the dead so they would share his distress, but no one came. On Friday, before anyone arose, he watched the appearance of nature again until he did not have the slightest doubt that it was Monday.

Then he grabbed a giant anchor and with the savage violence of his uncommon strength, he smashed to dust the equipment in the alchemy laboratory, the daguerreotype room and the silver workshop, shouting like a man possessed in some high sounding and fluent but completely incomprehensible language. He was about to finish off the rest of the galleon when Úrsula pleaded to the volunteers for help. Ten men in our motley group were needed to get him down on the ground, fourteen to tie him up, twenty to drag him to the giant Banyan tree, where we tied him up, barking a strange language spewing a green froth from his mouth.

Two Jamaicans came back several years later, collecting firewood and he was still tied to the Banyan tree by his hands and feet, soaked with rain and in a state of total innocence. They spoke to him and he looked at them without recognizing them, saying things that they did not understand. They untied his wrists and ankles, lacerated by the pressure of the old rigging ropes and left him tied only by the waist. Later on they built a shelter of palm fronds to protect him from the sun and the rain, but he retained that forlorn look of vegetarians.

Slowly something started to happen in my camping companion Angela’s mind during the third year of the rain, for she was gradually losing her sense of reality and confusing present time with remote periods of her life to the point where, on one occasion, she spent three days weeping deeply over the death of Petronila Iguaran, her great great grandmother, dead and buried for over a century

Angela at twenty three has the barely perceptible up tilting of the head that marks young women of the second generation of good schooling. Angela was aware for the first time that her gift for languages, her encyclopedic knowledge, her rare faculty for remembering the details of remote deeds and distant places without having been there were as useless as our empty propane tank. She was generally good natured and rolled with the punches concerning our, er..... current "situation", but man did Fernanda bug her.

Fernanda was a woman lost in the world. She had been raised in a gloomy city, where the sun was never seen, six hundred miles away from our galleon home, where her family had had investments in palm oil. During her childhood there was interminable discussion of the splendor of the family’s past. “We are immensely rich and powerful” her mother told her. “ One day you will be queen.” She believed it even though they were sitting at a long table with a linen tablecloth and silver service to have a cup of watered down hot chocolate and a day old sticky bun.

It was not innocence or delusions of grandeur, it was how she was brought up. Since she had the use of reason she remembered doing her business in a solid gold pot with the family crest on it. At fifteen, Fernanda, already beautiful, distinguished and discreet , was sent to a two hundred and fifty year old boarding school in Paris. After four years she had learned to write Latin poetry, play the clavichord, talk about falconry with gentlemen and apologetics with archbishops, discuss affairs of state with foreign rulers and affairs of God with the Pope.

When she returned home, all the furniture that was left in the mortgaged house was what was absolutely necessary, the silver candelabra and table service. Everything else had been sold one by one to underwrite the cost of her education. In one single day, with a brutal slap, life threw on top of her the whole weight of a reality that her parents had kept from her for so many years.

She tried to erase the scars of that strange joke by moving, and the details are another story for another time, to this isolated part of Hawaii and oddly enough, ending up camping with me, Angela and the rest of these….these people . But through the confusion of her indignation, through the fury of her shame, she maintained her unmistakable highland accent.

Fernanda walked throughout our compound complaining that her parents had raised her to be a queen only to have her end up as a servant in a madhouse, half zoo and half asylum. Most people in our encampment considered her a nuisance although in some way or another wanted to tell her that she could use that clavichord as an enema.

Suddenly, one day José Arcadio screamed from the Banyan tree, the rope around his waist moving up to his neck as he charged like a stallion, that the damnation of his family had come when it opened its doors to a stuck up highlander….just imagine it! And a bossy stuck up highlander bitch as well.

“Lord save us, a highland daughter of the same stripe as the highlanders the government sent to kill the banana workers,” and he was referring to no one but Fernanda, the godchild of the Duke of Alba, a lady of such lineage that she made the liver of president’s wives quiver, a noble dame of fine blood, who had the right to sign eleven peninsular names and who was the only mortal creature in this jungle camp of bastards who did not feel all confused at the sight of sixteen pieces of silverware: so that the libertine José Arcadio could die of laughter afterwards and say so many knives and forks and spoons were not meant for a human being but for a centipede.

Fernanda was the only one who could tell with her eyes closed when the white wine was served and on what side and in which glass and when the red wine was served and on what side and in which glass and not like that goddamned peasant Sukhmani, may she rest in peace, who thought that white wine was served in the daytime and red wine at night. She was the only one in the whole Hawaiian jungle that took care of her bodily needs in a golden chamber pot so that José Arcadio could have the effrontery to ask her with his Masonic ill humor where she had received that privilege.

And whether she did not shit shit but shat sweet basil?

Renata, a Guajiro Indian woman who arrived at our camp inflight from a plague of insomnia that had been scouring her tribe for several years, who through an oversight, had seen her toilet under the aloe bush, bellowed that even if the pot was all gold and with a coat of arms, what was inside was pure shit, physical shit, and even worse than any other kind because it was stuck up highlander shit.

Folks things had started to get weird on this little camping adventure. One day Angela entered Melquíades’ new rudimentary alchemy laboratory and did not leave for almost four years. In the lab, in addition to a profusion of pots, funnels, retorts, filters and sieves, there was a primitive water pipe, a glass beaker with a long thin neck, a reproduction of the philosopher’s egg and a still the gypsies had built themselves in accordance with the modern descriptions by the Jews of Amsterdam.

Along with those items, Melquíades left samples of the seven planets, the formulas of Moses and Zosimus for doubling the quantity of gold, and a set of notes and sketches concerning the processes of the Great Teaching that would permit those who could interpret the Sanskrit to undertake the manufacture of the philosopher’s stone.

Along with those items, Melquíades left samples of the seven planets, the formulas of Moses and Zosimus for doubling the quantity of gold, and a set of notes and sketches concerning the processes of the Great Teaching that would permit those who could interpret the Sanskrit to undertake the manufacture of the philosopher’s stone.

Melquíades took pleasure in showing his affection for Angela and the pleasure of her company by giving her exotic gifts: Portuguese sardines, Turkish rose marmalade, Virginia ham, and on one occasion a lovely Manila shawl. Melquíades, although a hundred and twenty years older than Angela, recognized that she seemed to have some penetrating lucidity that permitted Angela to see the reality of things beyond any formalism and confirm her impression that time was going in a circle.

In the smoky confines of the alchemy laboratory, he spoke to Angela with exaggerated enthusiasm about these people, without sentimentality, with a strict closing of his accounts of life, beginning to understand how much he really loved the people he hated the most. He confided in this white wanderer about the the only thing that he lamented was the fact that the idiots in the family lived so long.

Melquíades confessed that he was surprised at the unbridgeable distance that separated him from the family, even from the twin brother, sons of the same bitch, with whom he had played ingenious games of confusion in childhood and with whom he no longer had any traits in common. He drifted about, with no ties of affection, with no ambitions, like a wandering star in Ursula’s planetary system.

They were enamored by the same impermeability of affection. It was the price of their freedom, freeing them from a compromise that they had accepted not so much out of obedience as out of convenience. Melquíades and Angela had both dug deep into their hearts, searching for the strength that would allow them to survive the misfortune of this family and they discovered a reflective and just rage within each of them.

They were enamored by the same impermeability of affection. It was the price of their freedom, freeing them from a compromise that they had accepted not so much out of obedience as out of convenience. Melquíades and Angela had both dug deep into their hearts, searching for the strength that would allow them to survive the misfortune of this family and they discovered a reflective and just rage within each of them.

In reality Melquíades was not a member of the family, nor would he ever be of any other, since that distant dawn when Colonel Gerineldo Márquez took him to the barracks so he could see the execution of a banana worker. For the rest of his life he would never forget the sad and somewhat mocking smile of the the man being shot. It was not only his oldest memory, but the only one he had of his childhood,

While Angela studied the parchments and pondered the astrology textbook that Melquíades had bought in Barcelona, as fluency in many subjects would be required to complete the translation, I continued to live in the stone age. One day while I was feeding a panther we had captured in the jungle, a prophetic wind blew a young nameless artisan woman down the path who greeted me warmly and with a great deal of familiarity. In spite of time and distance she seemed to still love me very much.

The villagers, the volunteers and even José Arcadio did not pay any attention because they thought it was some new trick of the gypsies, coming back with their whistles and tambourines and their age old and discredited song and dance about the qualities of some concoction put together by a journeyman genius of Jerusalem.

The villagers, the volunteers and even José Arcadio did not pay any attention because they thought it was some new trick of the gypsies, coming back with their whistles and tambourines and their age old and discredited song and dance about the qualities of some concoction put together by a journeyman genius of Jerusalem.

The nameless artisan held in her hand, a solemn decree written on parchment and in Serbian. The profusion of meticulous and conventional vagueness, as she spoke for four days, seemed to tire the crowd. They wanted truth and insight into universal truths. She began with Adam and Eve and sobbed through the oldest sobs and woes in the history of mankind. She treated the classical writers with a household familiarity, as if they all had been her roommates at some period. It had never occurred to us until then to think that literature was the best plaything that had ever been invented to make fun of people.

She ended up recommending that we forget everything that we had been taught about the world and the human heart, that we spit on Horace, and that wherever we might be that we should always remember that the past was a lie, that memory has no return, that every spring gone by could never be recovered, and that the wildest and most tenacious love was an ephemeral truth in the end. That her taciturn father had to start thirty two armed uprisings, losing all thirty two of them, and had to violate all his pacts with death and wallow like a hog in the dung heap of glory in order to discover the privileges of simplicity almost forty years too late.

Melquíades had resolved to use his daguerreotype laboratory to obtain scientific proof of the existence of God. Through a complicated process of superimposed exposures, taken in different parts of our galleon village, he was sure he would eventually get a daguerreotype of God and put an end once and for all to the supposition of His existence.

Melquíades also got deeper into his interpretations of Nostradamus, staying up very late, suffocating in his faded velvet vest, scribbling with his tiny sparrow hands. He solicited Angela’s help with the translation and at first Angela gladly helped him in his work, enthusiastic over the novelty of the daguerreotypes and the predictions of Nostradamus, but communication was becoming increasingly difficult. He was losing his sight and his hearing, he seemed to confuse the people he was speaking with others he had known in remote epochs of mankind and he would answer questions in a complex hodgepodge of languages.

There was a wise Catalonian who had a bookstore in town where there was a Sanskrit primer. “You may have it” he said to Angela in Catalán. “The last person who used this book was Isaac the Blindman, so consider well what you are doing”.

With this book, Melquíades taught Angela how to read and write Sanskrit, initiated her in the study of the parchments and inculcated her a personal interpretation of what the white man’s banana company had meant to the village. The events that would deal the fatal blow to our time in the galleon village were just beginning to reveal themselves.

Angela did not leave Melquíades’ room for a long time. She learned by heart the fantastic legends of the crumbling parchments, the synthesis of the studies of Herman the Cripple, the notes on the study of alchemy, and apothecary, the keys to the philosopher’s stone, the secrets of Chaldean and Assyrian magic by Iamblichus, the Centuries by Nostradamus and his research concerning the plague so that she reached the age of thirty seven without knowing a thing about her own time but with the basic knowledge of an erudite medieval nun.

This endless study caused Angela to lose track of time. She had been accustomed to keeping track of the days, months and years using as points of reference the dates set for our return from the camping trip. But when Melquíades changed our departure date time and time again, the dates became confused, the periods were mislaid and one day seemed so much like another that we could not feel them pass.

Angela and Melquíades remained shut up in the room below deck, absorbed in the parchment, which they were slowly unravelling and whose meaning, nevertheless, they were unable to interpret. Úrsula would bring slices of Virginia ham and sugared flowers which left a spring like after taste in their mouths and on many occasions bottles of fine wine. At times they really seemed to get along splendidly.

Angela and Melquíades remained shut up in the room below deck, absorbed in the parchment, which they were slowly unravelling and whose meaning, nevertheless, they were unable to interpret. Úrsula would bring slices of Virginia ham and sugared flowers which left a spring like after taste in their mouths and on many occasions bottles of fine wine. At times they really seemed to get along splendidly.

This newfound harmony was interrupted by the death of Melquíades. Recently, a process of aging had taken place in him that was so rapid and critical that soon he was treated as one of those useless great grandfathers who wander about the house, dragging their feet, remembering better times aloud, and whom no one bothers about or remembers really, until the morning they find them dead in their bed.

One night, he called Angela in order to correct an important point of Sanskrit grammar and then suddenly he slumped over the parchments and died with his eyes open.

Eventually, the family and the villagers allowed us to bury him, not in any ordinary way, but with the honors reserved for the galleon village’s greatest benefactor. It was our first death and as such our first burial and the best attended one that was ever seen in this jungle town, only surpassed a century later, by Big Mama’s funeral carnival. We buried him right smack in the middle of a newly cleared area that was going to become our new cemetery. On a lava rock we wrote the only thing we knew about him: MELIQUÍADES

The crowds of adventurers who came from other jungle villages for the funeral overflowed and they bumped into each other among the gambling tables, shooting galleries, kiosks where the future was told and dreams were interpreted and tables of fried foods, beer, hallucinogenic mushroom teas and shots of pure cane liquor. After the funeral, they were bodies scattered about on the ground that were sometimes those of happy drunkards, but more often those of onlooking village people felled by shots, fists, knives and bottles during the brawls.

It was impossible to walk through the streets because of the furniture and dead animals and the scandalous behavior of dreadlocked American hippies, who hung their hammocks between the macadamia nut trees, amongst the lush green volcanic grass and the eucalypyus smoke from their cooking fires and fornicated in broad daylight and in front of everyone. The only quiet ones were the West Indian Negroes who sat in doors and sang melancholy hymns.

In the tumult of the last moments, the sad drunkards who carried Melquíades out got his coffin mixed up with that of a jaguars’ and hence buried him in the wrong grave.

It then fell on Angela to finish the translation. More than thirteen years had passed since Angela had learned the Sanskrit grammar in the book provided by the wise Catalonian when she translated her first sheet. It was not a useless chore, but it was only the first step along a road whose length was impossible to predict because the text in Sanskrit did not mean anything.The lines on the parchment were in code.

Angela began to decipher the parchments out loud to me, Úrsula and José Arcadio. The parchments were beginning to reveal themselves in coded lines of poetry. It was the history of the camping trip and our time in the galleon village, written by Melquíades, down to the most trivial details, written a hundred years ago. He had written it in Sanskrit, which was his mother tongue and he had encoded the even lines in a private cipher of the Emperor Augustus and the odd ones in Lacedaemonian military code.

The final protection that Melquíades had employed was the fact that he had not put events in the order of man’s conventional time, but had concentrated a century of daily episodes in such a way that they coexisted in one instant. The deciphering taught us that the history of the galleon village was a machine with unavoidable repetitions, a turning wheel that would have gone on spilling into eternity if not for the storm.

The final protection that Melquíades had employed was the fact that he had not put events in the order of man’s conventional time, but had concentrated a century of daily episodes in such a way that they coexisted in one instant. The deciphering taught us that the history of the galleon village was a machine with unavoidable repetitions, a turning wheel that would have gone on spilling into eternity if not for the storm.

The galleon village was already a fearful whirlwind of dust and rubble being spun about by the wrath of the biblical hurricane when Angela skipped eleven pages, so not to lose time with facts that she knew only too well. Amidst the apocalyptic funnel of debris, Angela began to decipher the instant that she was living, deciphering it as she, as we, lived it.

In the end it translated into a two hundred and twenty two page excursus, warning of the fickleness of passion.

Before reaching the final line she recognized immediately our fate and then she skipped ahead again to anticipate the predictions and ascertain the date and circumstances of our departure.

Before reaching the final line, however, she already understood that, metaphorically speaking, we would never leave that Hawaiian jungle village.

For it was foreseen that the village (or mirage) would be wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men at the precise moment when Angela would finish deciphering the parchments, and that everything written on them was unrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more, because people condemned to one hundred years of solitude do not have a second opportunity on this earth.

Alas sweet people, there was really nothing left to say between Angela and me, what could we say?

“The years nowadays don't pass the way the old ones used to” she would say, feeling that everyday reality was slipping through her fingers.

“What hurts me the most” she would say laughing, "is all the time that we wasted.”

“Oh, Ted my friend,” she sighed.” It’s enough for me to be sure that you and I exist at this moment. Who would have thought that we really would end up living like cannibals?”

We had both lost our sense of reality, the notion of time, the rhythm of daily habits, a decade ago.

I said I would drive the rental car back from Waipi’o Valley and she would take the train back to give her some time to mull things over. The least I could do after all this was buy her a ticket back to Hilo. I dropped her with one small backpack at the old deserted banana train depot.

I said I would drive the rental car back from Waipi’o Valley and she would take the train back to give her some time to mull things over. The least I could do after all this was buy her a ticket back to Hilo. I dropped her with one small backpack at the old deserted banana train depot.

As it pulled into the station, I noticed It was the longest train I had ever seen, with almost 2000 freight cars and a locomotive at either end and a third one in the middle, to which were connected two passenger cars. It had no lights, not even red and green running lights, and it slipped off with a nocturnal and stealthy velocity. On top of the cars I could see the dark shapes of the soldiers manning their sandbag emplaced tripod heavy machine guns.

It turns out that I had bought Angela an eternal ticket on a train that never stopped travelling. In the Instagrams and Facebook musings that she posted to us back at Kalani every now and then from various waystations, she would describe with glee the instantaneous images that she had seen from her coach window, as if she was tearing up and throwing into oblivion some long poem:

the chimerical negroes in the cotton fields of Louisiana, the winged horses in the bluegrass of Kentucky, the Greek lovers in the infernal sunsets of Arizona and the girl in the red sweater painting water colors by a lake in Michigan who waved at her with her brushes, not to say farewell but out of hope, because she did not know that she was watching a train passing by with no return.

the chimerical negroes in the cotton fields of Louisiana, the winged horses in the bluegrass of Kentucky, the Greek lovers in the infernal sunsets of Arizona and the girl in the red sweater painting water colors by a lake in Michigan who waved at her with her brushes, not to say farewell but out of hope, because she did not know that she was watching a train passing by with no return.

Angela would, from time to time, from year to year, write me that she would be back on Monday because she had to work in the kitchen at Kalani on Tuesday morning.

This Tedism, as usual, was inspired on one end, plagiarized on the other, by two books. I had started One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez several times since high school and only now did I have the time and temperament to finish it. Add to the mix my imagination, Hawaii, felonious artistic license and bits and pieces culled from The Death of the Great Spirit, An Elegy for the American Indian by Earl Shorris and voila! I present One Strange Camping Trip. Do yourself a fucking favor and google: Horace, philosopher's stone, daguerreotype, Isaac the Blindman, Herman the Cripple, Zosimos, the SS Victor Hugues and course, per omnia secula seculorum. A Hui Hou and aloha Angela and thanks for the time you took for the trip and hence great pictures. I hope this whole experience has not created any permanent psychological damage...it really was kinda freaky.

Comments